I consulted several recipes, including chicken skewers with nuoc cham (Food & Wine), gingery chicken satay with peanut sauce (ditto), Balinese chicken satay (Martha Stewart), beef satay (Chez Pim; a different meat, but peanut sauce does not discriminate), and pork satay with an appealingly simple marinade (Bon Appétit). I didn't end up following any of them; instead I improvised a recipe using what I had on hand. The result was a delicious satay that was a little Indonesian (by way of the kejap manis), a little Thai (by way of Golden Boy fish sauce — the radiant baby is my new favorite kitchen icon), and a little Balinese (by way of the coconut). I wouldn't present it to anyone as an authentic rendition of the cuisine of any of these cultures, of course, although it would be loads of fun to put together a comparative satay menu someday, wouldn't it?

There is no one right way to make satay. There's not even one way to spell it; in some places it is saté, and in South Africa it is sosatie. According to The Oxford Companion to Food, satay is

a dish of SE Asia, especially Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, which consists of small strips of meat, chicken, or fish threaded on to thin skewers . . . . Marinades vary from place to place but typically include dark soy sauce with lime juice, sugar, garlic and other seasoning. The common accompaniment for satay is a dipping sauce based on peanuts, pale brown in color. But other sauces may be used.

The entry goes on to quote Jennifer Brennan's Encyclopaedia of Chinese and Oriental Cookery on the origins of satay. Although it's often regarded as Indonesian, it did not spring up in Indonesia in a singular moment of genius:

Although both Thailand and Malaysia claim it as their own, its Southeast Asian origin was in Java, Indonesia. There satay was developed from the Indian kebab brought by the Muslim traders. Even India cannot claim its origin, for there it was a legacy of Middle Eastern influence.

A few comments on the recipe that follows: First, the only thing kecap manis has in common with ketchup, apart from the sound of the name, is that it comes in a bottle. I recommend picking up a bottle the next time you see one because it's got great flavor and a very nice texture - thick, smooth, glossy - but it is basically a sweet soy sauce, and you can substitute a mixture of soy sauce and brown sugar if you don't have it. (A low-sodium soy sauce would be preferable because the fish sauce will add plenty of salt to the recipe). Second, there isn't really a satisfactory substitute for fish sauce, and it's easy enough to come by (and versatile enough to be used up before it goes bad), so you might as well buy a bottle. Third, I used dried lemongrass, and I don't feel too bad about it - I'd rather use that than have woody bits of past-its-prime fresh lemongrass stuck between my teeth. If you have 2 stalks or so of tender fresh lemongrass, by all means use it, but if all that's readily available is dried-out and sad looking, use the dried stuff. Finally, I used light coconut milk. I do feel sort of bad about that because the flavor tends to be insipid, but have you looked at the fat and calorie content of regular canned coconut milk lately? There are some high calorie foods one can compromise on without suffering too badly, and for me coconut milk is sometimes one of them: I find it acceptable, for some recipes, to boost the flavor of light coconut milk with a spoonful or two of shredded unsweetened coconut. For a good curry, only the full-fat type will do, but for a marinade this mixture is a decent compromise.

I'm hesitant to suggest how many people this serves because it can be a first course or a main course or, for the industrious, a snack to have with drinks. Let's say it serves 3 to 6 people.

chicken satay with peanut sauce

1 1/4 lb. boneless, skinless chicken thighs, trimmed of fat and cut into strips suitable for threading on skewers (about 1 1/2" wide)

marinade:

2 serrano chiles, seeds and ribs removed, coarsely chopped

2 cloves garlic, peeled and chopped

1 heaping tbsp. shredded unsweetened coconut

1 heaping tsp. freshly toasted and ground coriander seeds

1 heaping tsp. grated fresh ginger

1 heaping tsp. powdered lemongrass (see comments above)

3/4 cup coconut milk (see comments above)

1 tbsp. kejap manis (substitute 1 tbsp. low-sodium soy sauce + 2 tsp. dark brown sugar)

2 tbsp. fish sauce

peanut oil for brushing pan or grill

peanut sauce:

1 tbsp. peanut oil

2 small cloves garlic (or 1 large), minced

1 heaping tsp. freshly toasted and ground coriander seeds

1 tbsp. shredded, unsweetened coconut

3/4 cup coconut milk

1/3 cup natural peanut butter

1 tbsp. kejap manis (see note above regarding substitute)

juice of 1/2 a lime

fish sauce, to taste

accompaniments:

crisp lettuce leaves

wedges of lime

chopped cilantro

coarsely chopped dry-roasted peanuts

equipment:

wooden skewers, soaked in water for 30 min. before ready to use

a broiler pan, a cast iron grill pan or a bbq grill

To make the marinade, put the chiles, garlic, shredded coconut and spices in a food processor and mix at full speed until they start to form a paste. Add the coconut milk, kejap manis and fish paste and mix until thoroughly combined. Put the chicken pieces in a large ziploc bag or shallow dish and pour the marinade over them. Marinate, tightly covered, in the refrigerator for at least 5-6 hours.

For the peanut sauce, heat the peanut oil in a small sauce pan over medium-high heat and sauté the garlic, the coriander, and the coconut until the garlic softens and the coriander and coconut are browned and very fragrant. (This will take just a minute or less). Add the coconut milk and bring to a boil. Stir in the peanut butter and the kejap manis until the sauce is smooth and remove the pan from the heat. Once the sauce has cooled down a bit, stir in the juice of half a lime and season to taste with the fish sauce. (I was happy with just a sprinkle of fish sauce, and added a pinch of salt as well; keep in mind that you won't be able to accurately taste for seasoning while the sauce is still very warm, and you can always add more later). The sauce is best made ahead of time and refrigerated; bring it to room temperature before serving.

Take the chicken out of the refrigerator approximately 15 min. before cooking. Take the skewers out of the water, pat them dry, and thread the chicken on the skewers. Brush a broiler pan, grill pan or bbq grill with peanut oil and broil or grill the chicken approximately 6-10 minutes, turning once during cooking. (The cooking time will depend on the thickness of your pieces of chicken; the juices should run clear, and if you're in doubt about whether the chicken is cooked through, cut into one of the thicker pieces and have a look at the inside).

Serve the skewers warm or at room temperature on plates lined with lettuce leaves, and sprinkled with chopped cilantro and chopped dry-roasted peanuts if you like. The sauce is most flavorful served at room temperature and can be either drizzled over the chicken or served in cups alongside it.

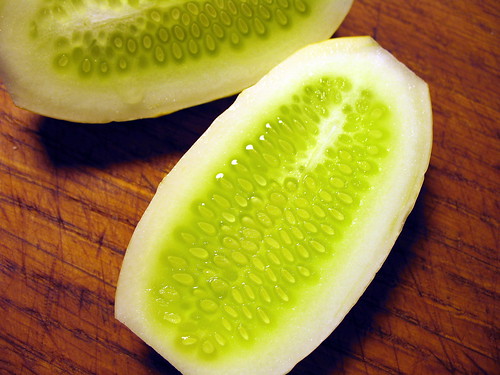

The peanut sauce is unphotogenic, as is the red cabbage, carrot and radish slaw I made. The delicate little cucumbers I picked up at the farmers' market yesterday morning, however, were gorgeous and needed nothing more than a sprinkle of coarse salt.

The recipe for the slaw needs to be refined, I think, but I'm posting the recipe anyhow because I think it's worth experimenting with. Most coleslaw recipes contain sugar and I think using kejap manis in its place is worth a try; it adds a subtle sweetness and it has a depth of flavor that white sugar lacks, almost like a savory, salty caramel. I used only red cabbage because that's what I had, but I think a mixture of green and red would look nicer and would have a more pleasing mix of textures. The recipe below makes more dressing than needed; the excess will keep in the refrigerator for a couple days in a tightly-covered container.

Red cabbage, carrot and radish slaw

2 tablespoons toasted sesame oil

juice of 1 lime

1/2 tsp. Sriracha sauce (red chile and garlic sauce), or more to taste

1 tbsp. kejap manis

1 tbsp. mayonnaise (recommended: Japanese brand Kewpie)

12 oz. red cabbage, shredded (see comments above)

1 carrot, peeled and shredded or sliced paper-thin

2 large red radishes, sliced paper-thin

2 tablespoons dry roasted salted peanuts, coarsely chopped

Whisk together the sesame oil and lime juice until emulsified and then whisk in the Sriracha sauce, the kejap manis and the mayonnaise. (Dressing can be made ahead of time and stored in the refrigerator in a tightly-sealed container).

Just before you're ready to serve the meal, toss together the cabbage, carrot and radishes with enough dressing to moisten them. Toss in the chopped peanuts, if using, and serve at once.

There was a dessert too, and it didn't quite work out. I thought it would be clever to make a sort of dessert spring rolls with blueberries and the filo dough I had left over from another recipe (coming soon in its own post), and I also thought it was quite possible that the filling would leak out during baking. I tried to prevent this by stirring a mixture of cornstarch and lime juice into the blueberries, with hopes that the juices would thicken and stay put, but I ended up with a bubbling blueberry puddle on my baking sheet. Fortunately I lined the baking sheet with parchment paper rather than a Silpat (I didn't want to have to scrub a sticky mess), and fortunately the results were quite edible anyhow. They just didn't have much filling on the inside.

What was left of the filling had a terrific flavor, and I'm going to use it again to fill something a little more sturdy before the summer's over: 1 pint of blueberries tossed with 2 tablespoons of turbinado sugar, plus 1 tablespoon of cornstarch that had been whisked together with the juice of half a lime until smooth, plus a generous pinch of cinnamon. It deserves a decent pastry shell.